Brutalists' Gold

There's no accounting for taste. But taste does have a particular potential in democratic society. Anyone can look down on anyone else. Those of us without very much can make any judgments we wish of what people do with a lot.

This is part of the appeal of the publicity that surrounded the Kennedys' Camelot, the '80s excess of Robin Leach, and the Real Housewives franchise today. If suddenly the audience had to a lot of money to deal with, we would have some propriety, some restraint and direction about what we did with it. We would have some sense that someone could see us like we see them, even if we are very unlikely to encounter such a change in fortune.

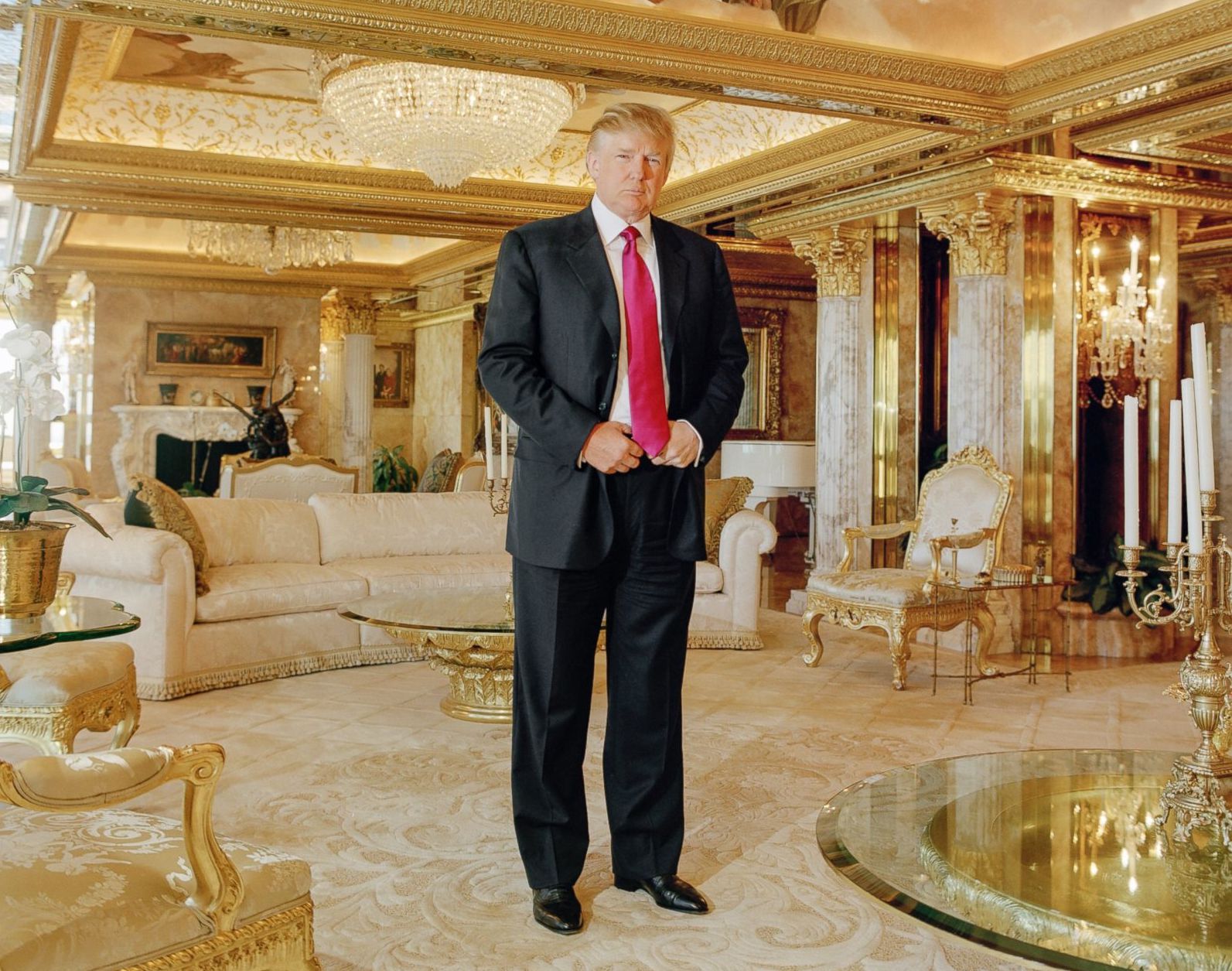

Part of the way many of us exorcise our horror and fascination at the phenomena presented by Donald Trump is through esthetic judgment. We're lucky that before he styled himself as the Mussolini of the outer boroughs, Trump attracted the scorn of discerning New York society for his irruptions on the Manhattan skyline. Tastemakers like Graydon Carter and Kurt Andersen have published their torments and slights of Trump's vulgarity and ignorance for us to enjoy in a way where we can be discerning downlookers for just the space of an article. And I do enjoy it. I really do. But not without questions.

The questions I ask are about what work the kind of elitist-populist derision at the new, crass, and un-rule-following does in a society in transition. Trump clearly thrives on the dynamic of envy and repugnance shown at his stuff, and now he's taking it to the political realm. But is that all there is?

My thinking about the politics of taste is anchored in a different society in transition: Vienna around the turn of the 20th century. Dramatic changes in urban space coincided with major esthetic disruptions. Josef Hoffmann was selling his spare and whimsical housewares and interiors to the upper bourgeoisie of the Ringstrasse. Vienna secession painters were staging a revolt against classical-imperial beauty and pious Christian humanism. The most historically-relevant reaction against this trend is of course its blatant antisemitism. The Nietszchean revulsion at degenerate art shaped the esthetic part of the fascist tradition Trump is nontrivially drawing on.

Obviously, we don't want a part of this in mocking the Trump's taste. Milan Kundera has contributed to an esthetics of the left that deals with the tension between resisting the imposition of kitsch while affirming the people (whatever that means). The well-known formulas of The Unbearable Lightness of Being center on the insight that authoritarian esthetics can't tolerate irony for its resistance to brute power.

We can certainly criticize Trump's spaces like this. The people hanging around Trump Tower, the Roger Aileses, Rudy Giulianis, and Newts Gingrich, are too scared, too fawning, or too greedy to tell the would-be dear leader that the reason Versailles is a museum today is not one that flatters the French monarchy and that Putin's photo gallery does not read as self-assured masculinity. That basic irony is clearly lost in what Trump makes.

But in the present moment, isn't irony a power form of its own? Doesn't it characterize kinds of preciousness and privilege not far enough removed from Trump's to be wholly something else? So further, is there any use of trying to disentangle and reconnect moral and political thought from esthetic judgment?

If only in the Trumpian moment, I can think of two suggestions. The political world Trump is presenting has no qualities of welcoming or inspiration. It's wholly hostile and totally unreflective. There is neither a place to make a home or a challenge to live differently. Not in the gilt banality of his skyscrapers and country clubs or his racist reimagining of a past that was more modest and decent.

This is a long way from a whole esthetic philosophy, of the left or not, but I think that as much fun as we might have laughing at or laughing off the ugliness and imposition the Trumps of the world represent, it pays to attend to the reasons we feel and use.